Contributed by sportswriter Paul Zanon

Debates about how one fighter would have fared against another from a bygone era are fairly common. Within the heavyweight category, you’ll often hear, ‘He would have been too small for the current day heavyweights.’ Standing at 6ft 1inch and weighing 87kg (or 13 and a half stone), Jack Dempsey once said, “Tall men come down to my height when I hit ’em in the body.” That was certainly the case when he won the world title in 1919.

Born William Harrison Dempsey on 24 June 1895, in the small Mormon town of Manassa, Colorado, young Jack was of Irish and Cherokee descent. For those of you with an interest in genealogy, rumour had it that Dempsey may have actually had Romanian roots.

Growing up in meagre surroundings, Dempsey lived a nomadic existence, following his family wherever the work was. By the age of 14, forced by poverty and hunger, Dempsey left school and started riding the rails on the undercarriage of trains, taking on a number of jobs, including mining, shining shoes, dishwashing, and saloon bouncing. Often living in austere and threatening environments, Dempsey soon became acquainted with street fighting, but also realised he had a natural talent for inflicting fistic punishment. Dempsey claimed to soak his face and fists in bull urine to strengthen his skin, which perhaps accounts for the lack of cuts throughout his boxing career.

Often answering the call for a pathetic purse or a free meal, ‘Kid Blackie,’ as he was known at the time, would fight fully grown adults. If a fight had been cancelled or he needed to earn a dollar, he would often walk into the local saloons or watering holes and say, "I can't sing and I can't dance, but I can lick any son of a bitch in the house."

Dempsey went on to say years later. “When I was a young fellow I was knocked down plenty. I wanted to stay down, but I couldn't. I had to collect the two dollars for winning or go hungry. I had to get up. I was one of those hungry fighters. You could have hit me on the chin with a sledgehammer for five dollars. When you haven't eaten for two days, you'll understand.” He certainly coined the phrase, ‘A hungry fighter.’

Dempsey made his debut on 18 August 1914 in Colorado Springs against Young Herman, walking away with a draw over six rounds. Less than three months later, on 2 November, he took on Young Hancock, who went by the name of ‘One Punch Hancock.’ Ironically, Dempsey knocked him out in the first round, with one punch.

From the time of his pro debut until November 1916, Dempsey fought 32 times, with only one loss. On 13 Feb 1917 Dempsey took on Hoboken born ‘Fireman Jim Flynn,’ who was 15 years Dempsey’s senior. To everyone’s amazement, Dempsey was knocked out in 25 seconds of the first round. This was his first and only knockout loss on his professional record, but one he would avenge. In fact, with the exception of his encounters with Gene Tunney later on in his career, ‘The Manassa Mauler’ would avenge all his losses.

Undeterred by the Flynn contest, Dempsey fought a further 12 times in the next 12 months, which included evening the score with Flynn, knocking out the New Yorker in similar fashion in the opening session.

Around this time, Dempsey approached a gentleman in Harlem, New York by the name of Jack Golomb to design and supply him with headgear and gloves that would last more than 15 rounds during training. Golomb had originally started the company to manufacture swimwear, but obliged Dempsey’s request.

Golomb also provided shorts with elastic waistbands, which up to that point were almost revolutionary as most boxers needed belts to hold them up. Rumour has it, that’s where the term, ‘Boxers shorts,’ evolved from in their modern day underwear form. The only issue was that Dempsey didn’t have enough money to cover Golomb’s services. Thankfully, the trusting tailor allowed him to take the merchandise on credit. Overwhelmed by the generosity and trust, Dempsey wore the same brand for the rest of his career. The name of Golomb’s company? Everlast.

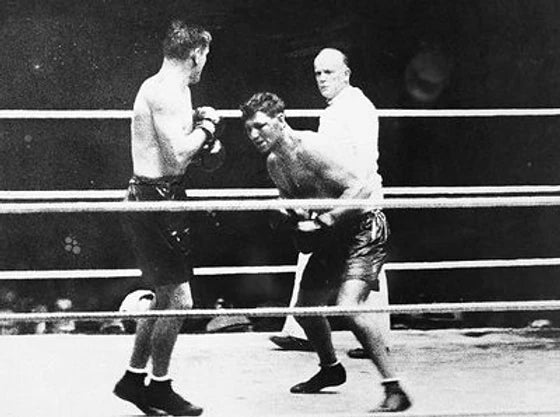

By 4 July 1919, Dempsey, now a prime physical specimen at 24 years of age, challenged the reigning heavyweight world champion. Jess Willard, the ‘Pottawatomie Giant,’ stood 6ft 6 ½ inches tall and weighed 245lbs, almost 60lbs more than Dempsey. He’d stopped the controversial and phenomenally talented former world champion, Jack Johnson two fights earlier. Despite coming off a period of inactivity, many thought Willard would walk right through the smaller and lighter man. The odds reflected the sentiments on fight day.

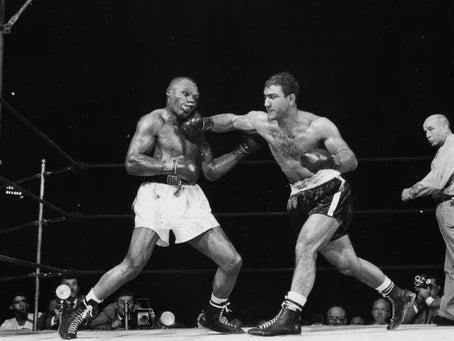

Speed, tenacity and leveraging power from his infamous crouch, Dempsey smashed Willard to pieces, knocking him down seven times in the opening stanza. Somehow, Willard lasted until the third round, at which point the referee rightly stepped in to halt proceedings. Very gracious in defeat, Willard suffered grotesque bruising, fractures to his face, broken ribs, a broken jaw and lost a number of teeth.

Dempsey defended his title five times over the next four years, with only one opponent lasting the distance. Two contests of note included a four round destruction of the endearing Frenchman and war hero, the reigning light heavyweight world champion, Georges Carpentier. The other, a clash with the ‘Wild Bull of the Pampas’ from Buenos Aires, Luis Firpo. The Argentine outweighed Dempsey by 24lbs and had a couple of inches’ height advantage.

In front of a capacity crowd of 85,000 people with tens of thousands waiting outside, Dempsey was floored in the opening seconds of the first round. In the next 90 seconds, Dempsey knocked down the Argentinian seven times yet in the dying seconds of the first session, Firpo cracked Dempsey with a solid shot to the chin, sending him flying through the ropes. With the assistance of those in attendance ringside and a rather generous late count from the referee, Dempsey was able to make it into round two, when Firpo was stopped after two further knockdowns. Before Hagler fought Hearns, this was possibly the biggest barnburner in live recorded history. An oil canvas painting by George Bellows encapsulates the moment Dempsey fell through the ropes.

Three years after Firpo, on 23 September 1926, Gene Tunney challenged Dempsey for his crown at the Sesquicentennial Stadium, Philadelphia, in front of over 120,000 people. The ring savvy Tunney used space, technique and masterful counter movement to take a confident points decision over 15 rounds and was crowned the new champion of the world. After the fight, Dempsey’s wife asked, ‘What happened?’ and he replied, ‘I forgot to duck.’

Ten months later, on 21 July 1927 Dempsey took on rising star, Jack Sharkey in a world title eliminator. Knocking out the future world champion in seven rounds, Dempsey had his sights firmly set on avenging his loss against ‘The Fighting Marine.’ Incidentally, Dempsey refereed Sharkey’s bout against ‘KO Christner’ 18 months later.

Back to the Tunney rematch. On 22 September 1927 at Soldier Field, Chicago, Dempsey was losing the fight on points, when in the seventh round he landed a peach of a left hook to Tunney’s chin, followed by a furious flurry, which sent the champion to the canvas. As the referee walked Dempsey to a neutral corner, Tunney was given the luxury of an estimated four to seven seconds breathing space, before the official referee’s count started. Getting up at the count of nine, Tunney weathered the storm. Despite the knockdown, Dempsey was unable to capitalise and the contest became engrained in history as ‘The Long Count Fight.’ That was Dempsey’s last fight as a professional boxer. He retired at the age of 32 with a record of 60-6-8.

In 1935, he opened Jack Dempsey's Restaurant in New York City, which proved to be hugely popular over its 39 year existence. With his good looks and links to the film industry, it was no surprise when Dempsey appeared on the big screen. He and his then wife, the glamorous Hollywood actress Estelle Taylor, both starred in the Broadway play, The Big Fight. He also appeared in a number of other films, including Sweet Surrender, The Prizefighter and the Lady.

His last knockout performance came as something of a surprise to him, but perhaps more so to those in the opposite corner. In the mid-1960s two thugs tried to mug Dempsey in Manhattan. Unaware of who the old man was, he rewarded one with a left and the other with a right hand, rendering them both unconscious with single shots.

Jack Dempsey died of heart failure on 31 May 1983, aged 87. In 1990 he was posthumously inducted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame, immortalising his existence in the square ring forever. Should you wish to pay homage to Manassa’s favourite fighting son, you can make the pilgrimage to the Jack Dempsey Museum, once his childhood home. The first person to greet you is an impressive bronze statue of the man himself.

Paul Zanon, has had nine books published, with almost all of them reaching the No1 Bestselling spot in their respective categories on Amazon. He has co-hosted boxing shows on Talk Sport, been a pundit on London Live, Boxnation and has contributed to a number of boxing publications, including, Boxing Monthly, The Ring, Daily Sport, Boxing News, Boxing Social, amongst other publications.