By Paul Zanon

“As a West Side kid fooling around with boxing gloves, I had been, for some reason of temperament, more interested in dodging a blow than in striking one.”

Gene Tunney

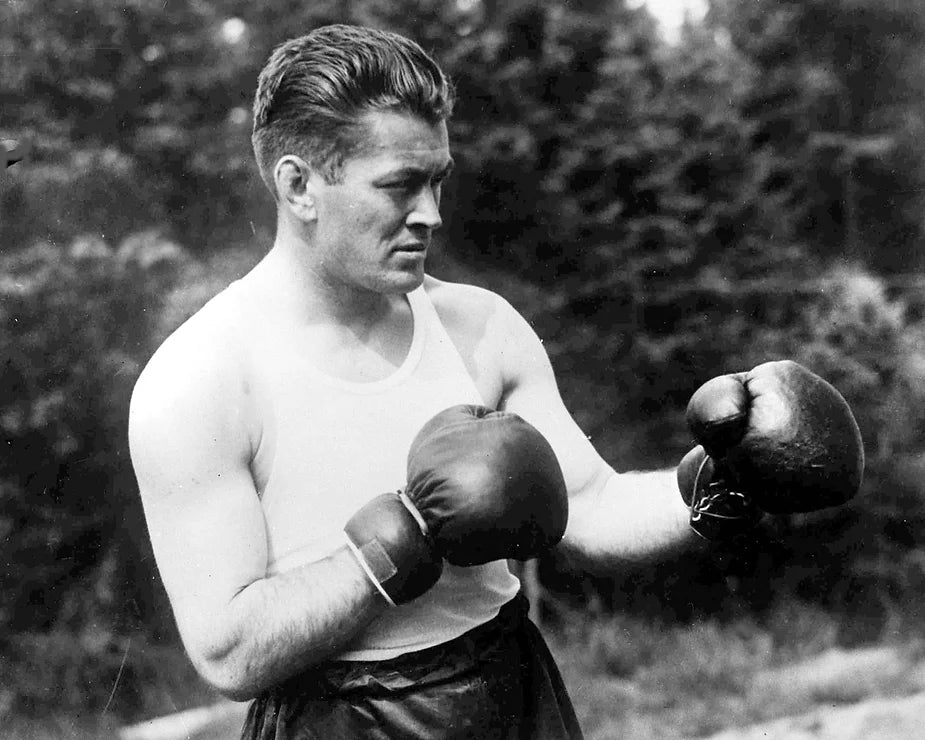

James Joseph Eugene Tunney, the eldest of seven siblings was born on 25 May 1897 in New York City. Rumour has it his youngest sister had problems pronouncing his name and instead called him Gene. The name endearingly stuck.

When John and Mary Tunney emigrated from County Mayo, Ireland to America in 1880, their intention was to give their future family a stable life and bring them up with the correct moral values. John Tunney had boxed back in Ireland and enjoyed attending shows in New York on his arrival to America, but he had hopes his first son would eventually be a man of the cloth. That all changed when one day he found out Gene was being targeted by bullies on his walk back from school and decided to teach him how to box. A self-defence lesson soon spiralled into an unparalleled passion and by the age of 10, Tunney was given his first pair of boxing gloves from his father and waved goodbye to the priesthood.

A local boxing trainer, Willie Green taught Tunney the fundamentals of boxing at Greenwich Village Athletic Club and by 16 he started competing in the amateur ranks. Tunney was a different kind of fighter than the classic brawling boxer from the turn of the twentieth century. He loved to read and write, was intrigued with the science behind physical fitness and nutrition, and his friendship circle would go on to include the likes of George Bernard Shaw and Ernest Hemmingway. At a time when heavy drinking, smoking and living life to excess were seen as fashionable indulgences, being a scholar and a boxer were an unattractive paradox.

By the age of 17, Tunney had matured into a fine figure of a man who stood 6ft tall and had movie star good looks. On 3 May 1915 he made his debut in New York against Bobby Dawson, in a contest scheduled for 10 rounds. After being floored in the seventh round, Dawson failed to come out for the eighth, whilst Tunney embarked on a destructive winning streak behind a sharp boxing brain and a destructive right hand.

From 1915 – 1921, Tunney amassed 41 victories, two draws and no losses. One fight of note was on 2 July 1921 against a Canadian by the name of Soldier Jones. The opponent was not so important for Tunney, but the occasion and the performance was where the focus hinged as he fought on the undercard of Jack Dempsey versus Georges Carpentier for the world heavyweight title and was hoping to get the attention of all those in attendance. Unfortunately, Tunney’s performance was far from eye catching as the New York Times reported. “Tunney appeared off-form and unimpressive. Jones was a slow moving and wild-swinging novice without any apparent knowledge of boxing." Tunney’s chance would come later against both champions.

Whilst Tunney was battling in the ring, the rest of the planet was locking horns in the First World War. Eager to serve his country, in 1918 Tunney enlisted into the Marine Corps, serving as a private in the 11th Marine Regiment in France, mainly guarding airplane hangers before moving on to Rhineland in Germany the year after. During this time he fought on the Marine boxing team and went on to become the U.S. Forces Expeditionary light heavyweight champion. Despite being discharged after the war, he remained part of the Marines Corps reserve, attaining the rank of major in the Connecticut Naval Militia.

Whether he was fighting at a Regiment Armory or the National Sporting Club in Paris, France, Tunney’s boxing career remained very active despite of the war, and even gained him the moniker of ‘The Fighting Marine.’ By 13 January 1922, Tunney had fought 43 times, but not against fighters of any note. However, legendary promoter Tex Rickard ensured that all changed as he put Tunney in with ring veteran and former world light heavyweight champion, Battling Levinsky at Madison Square Garden for the American light heavyweight title.

Levinsky had fought 245 times by this point and had mixed in good company, including Jack Dempsey and weighed in a pound over the light heavyweight limit, compared to Tunney who came in a touch over 170lbs. Despite his experience, it was Levinsky who was schooled that night, as Tunney secured a very wide points decision. The lacklustre performance against Soldier Jones was forgiven as Tunney had now gained the attention of the media, promoters and fans.

After racking up four further victories in three months, on 23 May 1922 The Fighting Marine was pitted against the Pittsburgh Windmill at Madison Square Garden. By this stage, Harry Greb had amassed 221 fights, fought in multiple weight divisions, reportedly gave Jack Dempsey a torrid time in sparring and was simply the man to avoid. At only 5ft 8in, 27 year old Greb hadn’t come to make up the numbers. Despite weighing in a little over the modern day middleweight limit, giving away around 15lbs to Tunney, Greb lived up to his moniker, swarming his man at a ferocious pace to secure a points victory over 15 rounds. The Pittsburgh Post reported: ‘Tunney fought extremely well. He made a great fight for 10 rounds, but Greb set a pace in the last five that overwhelmed Gene. Tunney's eyebrows were cut and he bled at the nose and mouth. Greb fought his usual fight, all over his man, and chopping him up. Tunney fought Greb much better than Tommy Gibbons had done in New York.’ It was later confirmed that Tunney’s nose was broken in the first round from a headbutt and despite losing the fight, he gained several new fans as he bit down on his gumshield and traded with Greb to the final bell.

On a side note, it’s worth mentioning that Greb had sustained a terrible eye injury in 1921 and fought the balance of his 300 fight career pretty much out of one eye, including this victory over Tunney. On retirement, Greb needed a number of surgeries relating to his boxing career and his wild passion for cars. He eventually had his eye replaced with a glass prosthesis in 1928, but sadly, very shortly after, whilst undergoing another injury related procedure, he passed away from complications on 22 October 1926. He was only 32.

The Greb loss would be Tunney’s only mark on his otherwise unblemished record and he used the contest to improve his knowledge and return a far more polished and determined fighter. Despite many, include Tex Rickard strongly advising Tunney to steer clear of a rematch with Greb, that’s all the marine wanted. After fighting a further nine times in nine months without loss, the pair met on 23 February 1923 back at Madison Square Garden. Despite avenging the loss with a classic counterpunching performance, gaining a narrow points victory, the majority of those in attendance, including most of the reporters, had Greb winning comfortably. Tunney had retrieved his American light heavyweight strap, but he was far from impressed with his performance. Inevitably, the pair would meet again.

Ten months later, the third instalment of Tunney versus Greb happened on 10 December 1923. Greb was now near the full light heavyweight limit and was determined to gain back his belt, in addition to weighing the 2-1 tally in his favour. Despite a typically feisty and spirited performance from Greb, which included landing more punches than Tunney, the general consensus was that the punches landed by Tunney were far cleaner and more powerful. Not a landslide by any stretch, but Tunney was seen as winning nine of the 15 rounds comfortably, with very few of those in attendance disputing the decision.

Six fights later, on 24 July 1924, Tunney took on Frenchman Georges Carpentier. Paris’s favourite fighting son was three years Tunney’s senior and first appeared on the professional boxing circuit in 1908 at a mere 14 years old. By the time he fought Tunney, he had fought almost 110 times, had reigned as the light heavyweight world champion and won plaudits across three weight divisions from middle through to heavy. A definitive win for Tunney would add that all important propulsion to move closer to another heavyweight world title shot.

In front of a 30,000 strong crowd at the Polo Grounds, New York, Tunney handed Carpentier a beating, knocking him down three times in the tenth round and once again in the fourteenth. Soon after the bell rang for the final round, the referee intervened seeing that Carpentier was in no condition to continue and halted the fight.

Two fights and two months later, Tunney and Greb had their fourth encounter at the Olympic Arena, Brooklyn. One would assume that Tunney would have had the upper hand based on their last clash and also his performance against Carpentier, but one would be wrong. The 10 round contest was declared a draw by the referee, but pretty much every publication which covered the event had Greb the winner after the final bell. There was only one thing for it. A fifth and final dust up.

On 27 March 1925, Tunney and Greb met for another 10 rounds of action at the Auditorium, Saint Paul, Minnesota. This time round, the Pittsburgh Windwill couldn’t get in his rhythm. Associated Press said, Tunney gave Greb as thorough a beating as he has ever received. So completely was Greb outclassed and outfought in six of the ten rounds that he resorted to a defensive fight after the third and thereafter was guilty of persistent holding and stalling varied only by rare flashes of offensive fighting, which Tunney quickly terminated by a devastating attack. Tunney concentrated his fire almost entirely on Greb's heart and body, landing with deadly accuracy and telling effect. After a flashy start, Greb went on the defensive and let entire rounds go by without making more than a weak show of attack, without landing a decisive punch, even on those rare occasions when he undertook to do the leading."

Just in case you were assuming Greb was washed up by now because he’d fought around 270 times as a pro, it’s worth noting he won the world middleweight crown four months after the Tunney contest and only lost twice in his remaining 30 fights. Washed up he wasn’t.

The pair had fought 65 rounds over the years. Greb at a later date said, “Tunney had a lot of class, but he don’t stand still. He was behind me most of the time!” From a man as tough and proficient as Greb, those were compliments for Tunney to cherish.

Tunney’s camp was now making noises to challenge the world heavyweight champion, Jack Dempsey. The step up by most was seen as suicide for ‘The Big Bookworm,’ as Dempsey once referred to him. Many believed that the Manassa Mauler’s savage attacks would see the light heavyweight quickly dispatched in the early rounds. Tunney had other plans.

Now fighting a little north of 180lbs, three months later Tunney mad a massive statement disposing of Tommy Gibbons in the twelfth round. Gibbons had beaten Carpentier and lasted the distance with Dempsey when challenging for his title. It was now a matter of when he would fight Jack as opposed to ‘if.’ After knocking out four of his next five opponents, the stage was set for Tunney versus Dempsey on 23 September 1926 at Sesquicentennial Stadium, Philadelphia.

Dempsey stood an inch taller than Tunney and weighed 190lbs, only half a pound more than the challenger, who entered the ring in sensational shape. Attended by just under 121,000 fans, from the opening bell, Tunney controlled the fight and the champion through his technical ability and unwavering game plan. When his hand was raised as the new heavyweight world champion, few disputed the validity of the decision.

The Dempsey rematch, a year later almost to the day at Soldiers Field, Chicago was a more memorable affair. In the seventh round, in front of over 100,000 spectators Dempsey knocked down Tunney heavily, but stood over his opponent instead of walking to a neutral corner. Consequently, Tunney benefitted from an extra five or six seconds before the official count started. The knockdown would be engrained in history as ‘The Long Count,’ with the total canvas time for Tunney being around 15-16 seconds. The truth is, Tunney was temporarily hurt, but not badly stunned and could have most likely made the 10 count with no issues. Years later, Dempsey complimented the victor by stating he wasn’t sure if he could have beaten him, even at his peak. Tunney said of the Dempsey fight. “I did six years of planning to win the championship from Jack Dempsey.”

Ten months later, Tunney had his swansong against ‘The Hard Rock From Down Under,’ New Zealander Tom Heeney. The Kiwi put on a brave show, but Tunney broke him down in the later rounds and stopped him in the eleventh stanza. Despite Dempsey being in Heeney’s corner, both Jack and Gene went on to strike up a very close lifelong friendship over the coming five decades.

Retiring as world heavyweight champion is a feat only achieved by an elite few, including Rocky Marciano, Vitali Klitschko and Lennox Lewis. Tunney retired and never succumbed to the temptation that so many great fighters have fallen foul of. In addition, he’s only one of a handful as a heavyweight champion to have never been stopped.

1928 was a big year for Tunney. In addition to retirement, he was named The Ring Magazine’s Fighter of The Year. In fact, this was the first time The Ring had ever nominated a fighter for the honour. He also married granddaughter of billionaire George Lauder, Mary Lauder who he remained with until his death, giving them 50 great years together. They had four children, one of whom, John, became a U.S. senator. Lauder would eventually pass away in 2008, five days shy of her 101st birthday.

Despite marrying into one of the wealthiest families on the planet, Tunney carved his own trail of success as a very astute businessman, not to mention having his own healthy stash of money he had amassed as a boxer. The Fighting Marine relished any challenge posed to him, whether it be scientific, financial or philanthropic. He was also a very proud servant of his country and when America entered World War II in December 1941, Tunney was commissioned by the U.S. Naval Reserve as a lieutenant commander, in charge of setting up a programme of physical fitness – something he committed to for the balance of the war. During his service in the military, Tunney amassed a substantial number of honours, including the Naval Commendation Medal.

On 27 November 1978, Gene Tunney died in Greenwich hospital, suffering from a circulation related condition. He was buried at Long Ridge Union Cemetery in Connecticut. On hearing the news of Tunney’s passing, his former foe, Jack Dempsey had this to say. “I feel like a part of me is gone,” he said. “Because I was three years older than Gene, I always thought I would be the one to go first. As long as Gene was alive, I felt that we shared a link with that wonderful period of the past. Now I feel alone.” (New York Times)

In a career spanning 13 years, Tunney won 65 of his 68 contests by stoppage, with only one loss and two draws. By any standards, a very impressive resume. Tunney was a defensive genius with phenomenal footwork who was continually executing strategy for every second of a fight, whilst possessing an abundance of courage and knockout power in both hands. He conquered the great Jack Dempsey to become heavyweight world champion, but incredibly, never claimed the light heavyweight strap, despite being one of the best 175lbs fighters in history. Tunney was inducted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame in 1990 alongside a great list of fighters, including Jack Dempsey, Muhammad Ali and Joe Frazier. Even after passing, he remained in good company.

Paul Zanon, has had 11 books published, with almost all of them reaching the No1 Bestselling spot in their respective categories on Amazon. He has co-hosted boxing shows on Talk Sport, been a pundit on London Live, Boxnation and has contributed to a number of boxing publications, including, Boxing Monthly, The Ring, Daily Sport, Boxing News, Boxing Social, amongst other publications.