The flexing of regimental muscle for those stationed with the British Army in Rawalpindi, Pakistan, during the early 1900’s was, in the main, compulsory. The men would be divided into groups, handed hefty leather gloves and trade blows under the searing skies, dry and energy sapping heat of the Punjab.

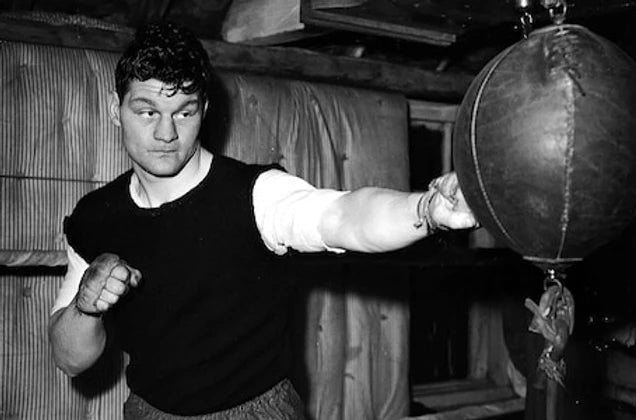

It was here, stationed with the Royal Artillery in 1906 that East Ender William Thomas Wells A.K.A 'The Bombardier' Billy Wells would hone his boxing skills, forge the heavy artillery he'd soon carry in both fists, and as time passed sculpt his celebrated muscular frame - the delivery system responsible for 40 KO’s throughout his career.

These same conditions produced many other tough men, Gunner Moir was one; thick set, heavily tattooed, who three years’ prior had bulldozed his way to the British Army heavyweight title in India. Now back in Blighty 1906, Moir was the incumbent British Heavyweight champion.

Although just 17yrs at the time Wells quickly made a name for himself showcasing his boxing ability. Divisional victories in 1908 confirmed his pedigree - as his star rose so did his rank, by 1909 he was promoted to Bombardier, in full time training, and with the help of a civilian coach became the All-India Champion. As news of his victories swept the regiments, he would simply be referred to as the ‘Bombardier’ such was his emerging celebrity.

Back in Britain the appetite for boxing as a spectator’s sport had grown, having proved his ability as a first rate boxer Wells sought to capitalise on his recent success, and return home, turning professional. Having bought himself out of the Army he would enter his first paid contest as the ‘Bombardier’ Billy Wells on the 8th June 1910 against Gunner Joe Mills, winning on points over six rounds. Wells would beat his next opponent by TKO, then rack up five straight knockouts setting him on a collision course with none other than Gunner Moir on 11th January 1911.

Moir by this time had been brutally knocked out by Canadian Tommy Burns in London for the heavyweight championship of the world in Dec 1907, then in his next fight lost his British heavyweight title in April 1909 to Iron William Ian Hague again by knockout. Meeting the unbeaten ‘Bombardier’ in the battle of former British Army boxing champions stirred something primal in Moir, a scalp that could potentially reinvigorate his flagging career. Seizing the opportunity Moir handed Wells a brutal 3rd round KO and with it, for now, military spoils.

Wells would shrug off the defeat, ripping the title from Moir’s former conqueror Iron William Ian Hague for the British heavyweight title on the 24th April 1911 at the National Sporting Club, Covent Garden, London, in the process becoming the first heavyweight to win the Lonsdale belt.

His win earned him a shot at the heavyweight championship of world against the inimitable, flamboyant and charismatic Jack Johnson scheduled for the 2nd October 1911 in London. Johnson, in 1908, had become the first African American heavyweight champion of the world, humiliating Tommy Burns in Sydney Australia for the title, then destroying all-comers including middleweight champion of the world Stanley Ketchel, followed by ‘fight of the century’ against the ex champion Jim Jeffries, victories that would disrupt the status quo, sending reverberations around the world in what was a time of virulent, overt racism, of the popular and institutional kinds. Johnson became an instant hero to people of colour around the globe and a symbol of the struggle against white supremacy. Fight films of Johnson beating white men became explosive material, visual conformation of Johnson’s physical dominion over his white counterparts, an effrontery and explicit threat to the white universe. To say Johnson was a pioneer would be an understatement.

Wells was cast, as a ‘white hope’ the first time a British boxer had been fitted with the moniker, a title he neither courted nor embraced, but he accepted the challenge to fight for the title. The proposed fight drew controversy as soon as it was announced with opposition and protest that travelled all the way to the top of the British government. The received wisdom at the time was the fight constituted a ‘breach of the peace’. Religious groups were up in arms citing the immorality of prize-fighting, when in truth, the underlying narrative was overtly racist and disapproving of contests between the races. The campaign reached the attention of the Home Secretary, Mr Winston Churchill, who upon reading a petition set before him banned the fight, declaring the contest ‘illegal’ ‘on the grounds of ‘public order’. The fighters and their management were served with an injunction and the matter went to court. Through various legal instruments and obstructions, the fight was cancelled. The entire debacle was symptomatic of the fear engendered by Johnson, laying bare the bigotry of the time. It would be the fight that never was.

Wells would go onto fight and gain his second title, the British Empire Heavyweight title in December 1911, knocking out Fred Storbeck in six rounds. Between 1911-1919 Wells beat all domestic opposition. There would be a final encounter with his old nemesis Gunner Moir in 1913. Defending his British title, Wells would inflict a sweet, painful revenge on the hapless Moir laying him flat in five rounds, restoring his superiority over the tough Lambeth man, and sending him into permanent retirement.

In total Wells defended his title 14 times. The caveat to all the success on home soil during this period was tempered by heavy defeats to foreign fighters. The great French heavyweight George Carpentier knocked Wells out on two occasions in 1913 for the European Heavyweight title and top quality Americans Al Palzar (1912) and Gunboat Smith (1913) would both KO the 6’3 Englishman as well as Frank Moran (1915) It appeared, although possessing great power, he fell short when faced with elite competition, lacking the punch resistance against the big hitters. This would not detract from the fact that he was an elite sportsman, with a ‘scientific’ boxing brain and heavy hands.

In 1915 he volunteered for military service with the Welsh regiment, where he was promoted to rank of Sergeant, however he continued to defend his heavyweight titles throughout this period.

Wells spent a short time organising physical training for the troops at Shoreham Army Camp, having made a name himself in physical instruction following the success of his first book ‘Modern Boxing: A Practical Guide to Present Day Methods’. He was somewhat ahead of his time and understanding the value his was providing went on produce a second book, after he retired in 1925, called ‘Physical Energy’. Wells put his career on hold from Dec 1916 to during the Great War while being stationed in France in 1917, continuing his physical training of the troops.

It was business as normal after the war with three straight wins on his return to the ring, then on the 27th February 1919 he finally lost his titles to Joe Beckett by KO in 5 rounds, a man he’d beaten in a non-title bout in his previous contest. He would rack up another 5 wins and challenge Beckett again but would be despatched in 3 rounds this time. He would win 5 of his last 8 fights, finishing a distinguished career with 48 wins 11 losses, no draws.

At the time of his retirement in 1925, Wells was one of the most identifiable Englishmen in the world, his sporting achievements and involvement in the high profile news story with Jack Johnson back in 1911 ensured that he was instantly recognisable - this coupled with his undeniable, dramatic physical presence brought him to the attention of the British film production house, the Rank Organisation in 1935. Those of a certain vintage will recall Rank’s iconic company trademark, a muscular torso of a man striking a gong twice, a melodramatic prelude to the film beginning. Billy Wells was considered to be the perfect replacement for the incumbent Carl Dane, and would be seen striking the gong for years to come.

Wells would foray into acting (not uncommon for sportsmen of the era) enjoying critical acclaim on the boards as Jack Bandon, the hero of a play called Wanted-A-Man. His success led to film roles, but it was as the ‘gong man’ that would define his on screen presence.

The ‘Bombardier’ Billy Wells passed away on the 12th June 1967. Remembered as a true, authentic gentleman, model of probity and a first class boxer.

It was here, stationed with the Royal Artillery in 1906 that East Ender William Thomas Wells A.K.A 'The Bombardier' Billy Wells would hone his boxing skills, forge the heavy artillery he'd soon carry in both fists, and as time passed sculpt his celebrated muscular frame - the delivery system responsible for 40 KO’s throughout his career.

These same conditions produced many other tough men, Gunner Moir was one; thick set, heavily tattooed, who three years’ prior had bulldozed his way to the British Army heavyweight title in India. Now back in Blighty 1906, Moir was the incumbent British Heavyweight champion.

Although just 17yrs at the time Wells quickly made a name for himself showcasing his boxing ability. Divisional victories in 1908 confirmed his pedigree - as his star rose so did his rank, by 1909 he was promoted to Bombardier, in full time training, and with the help of a civilian coach became the All-India Champion. As news of his victories swept the regiments, he would simply be referred to as the ‘Bombardier’ such was his emerging celebrity.

Back in Britain the appetite for boxing as a spectator’s sport had grown, having proved his ability as a first rate boxer Wells sought to capitalise on his recent success, and return home, turning professional. Having bought himself out of the Army he would enter his first paid contest as the ‘Bombardier’ Billy Wells on the 8th June 1910 against Gunner Joe Mills, winning on points over six rounds. Wells would beat his next opponent by TKO, then rack up five straight knockouts setting him on a collision course with none other than Gunner Moir on 11th January 1911.

Moir by this time had been brutally knocked out by Canadian Tommy Burns in London for the heavyweight championship of the world in Dec 1907, then in his next fight lost his British heavyweight title in April 1909 to Iron William Ian Hague again by knockout. Meeting the unbeaten ‘Bombardier’ in the battle of former British Army boxing champions stirred something primal in Moir, a scalp that could potentially reinvigorate his flagging career. Seizing the opportunity Moir handed Wells a brutal 3rd round KO and with it, for now, military spoils.

Wells would shrug off the defeat, ripping the title from Moir’s former conqueror Iron William Ian Hague for the British heavyweight title on the 24th April 1911 at the National Sporting Club, Covent Garden, London, in the process becoming the first heavyweight to win the Lonsdale belt.

His win earned him a shot at the heavyweight championship of world against the inimitable, flamboyant and charismatic Jack Johnson scheduled for the 2nd October 1911 in London. Johnson, in 1908, had become the first African American heavyweight champion of the world, humiliating Tommy Burns in Sydney Australia for the title, then destroying all-comers including middleweight champion of the world Stanley Ketchel, followed by ‘fight of the century’ against the ex champion Jim Jeffries, victories that would disrupt the status quo, sending reverberations around the world in what was a time of virulent, overt racism, of the popular and institutional kinds. Johnson became an instant hero to people of colour around the globe and a symbol of the struggle against white supremacy. Fight films of Johnson beating white men became explosive material, visual conformation of Johnson’s physical dominion over his white counterparts, an effrontery and explicit threat to the white universe. To say Johnson was a pioneer would be an understatement.

Wells was cast, as a ‘white hope’ the first time a British boxer had been fitted with the moniker, a title he neither courted nor embraced, but he accepted the challenge to fight for the title. The proposed fight drew controversy as soon as it was announced with opposition and protest that travelled all the way to the top of the British government. The received wisdom at the time was the fight constituted a ‘breach of the peace’. Religious groups were up in arms citing the immorality of prize-fighting, when in truth, the underlying narrative was overtly racist and disapproving of contests between the races. The campaign reached the attention of the Home Secretary, Mr Winston Churchill, who upon reading a petition set before him banned the fight, declaring the contest ‘illegal’ ‘on the grounds of ‘public order’. The fighters and their management were served with an injunction and the matter went to court. Through various legal instruments and obstructions, the fight was cancelled. The entire debacle was symptomatic of the fear engendered by Johnson, laying bare the bigotry of the time. It would be the fight that never was.

Wells would go onto fight and gain his second title, the British Empire Heavyweight title in December 1911, knocking out Fred Storbeck in six rounds. Between 1911-1919 Wells beat all domestic opposition. There would be a final encounter with his old nemesis Gunner Moir in 1913. Defending his British title, Wells would inflict a sweet, painful revenge on the hapless Moir laying him flat in five rounds, restoring his superiority over the tough Lambeth man, and sending him into permanent retirement.

In total Wells defended his title 14 times. The caveat to all the success on home soil during this period was tempered by heavy defeats to foreign fighters. The great French heavyweight George Carpentier knocked Wells out on two occasions in 1913 for the European Heavyweight title and top quality Americans Al Palzar (1912) and Gunboat Smith (1913) would both KO the 6’3 Englishman as well as Frank Moran (1915) It appeared, although possessing great power, he fell short when faced with elite competition, lacking the punch resistance against the big hitters. This would not detract from the fact that he was an elite sportsman, with a ‘scientific’ boxing brain and heavy hands.

In 1915 he volunteered for military service with the Welsh regiment, where he was promoted to rank of Sergeant, however he continued to defend his heavyweight titles throughout this period.

Wells spent a short time organising physical training for the troops at Shoreham Army Camp, having made a name himself in physical instruction following the success of his first book ‘Modern Boxing: A Practical Guide to Present Day Methods’. He was somewhat ahead of his time and understanding the value his was providing went on produce a second book, after he retired in 1925, called ‘Physical Energy’. Wells put his career on hold from Dec 1916 to during the Great War while being stationed in France in 1917, continuing his physical training of the troops.

It was business as normal after the war with three straight wins on his return to the ring, then on the 27th February 1919 he finally lost his titles to Joe Beckett by KO in 5 rounds, a man he’d beaten in a non-title bout in his previous contest. He would rack up another 5 wins and challenge Beckett again but would be despatched in 3 rounds this time. He would win 5 of his last 8 fights, finishing a distinguished career with 48 wins 11 losses, no draws.

At the time of his retirement in 1925, Wells was one of the most identifiable Englishmen in the world, his sporting achievements and involvement in the high profile news story with Jack Johnson back in 1911 ensured that he was instantly recognisable - this coupled with his undeniable, dramatic physical presence brought him to the attention of the British film production house, the Rank Organisation in 1935. Those of a certain vintage will recall Rank’s iconic company trademark, a muscular torso of a man striking a gong twice, a melodramatic prelude to the film beginning. Billy Wells was considered to be the perfect replacement for the incumbent Carl Dane, and would be seen striking the gong for years to come.

Wells would foray into acting (not uncommon for sportsmen of the era) enjoying critical acclaim on the boards as Jack Bandon, the hero of a play called Wanted-A-Man. His success led to film roles, but it was as the ‘gong man’ that would define his on screen presence.

The ‘Bombardier’ Billy Wells passed away on the 12th June 1967. Remembered as a true, authentic gentleman, model of probity and a first class boxer.