By Paul Zanon

‘A boxing match is like a cowboy movie. There’s got to be good guys and there’s got to be bad guys. And that’s what people pay for – to see the bad guys get beat.’

The ‘Phantom Punch,’ the mysterious death, mob ties and the biggest fists in boxing. Charles L. Sonny Liston certainly left his mark.

If you grew up in the Mike Tyson era, it’s hard to forget the intimidation the New Yorker brought to the ring. The stare downs, the look of pure rage and destruction and that presence of invincibility. However, he wasn’t the pioneer of said aura. About three decades prior, Liston was a widely avoided contender with bad intentions. If his opponents weren’t broken mentally before stepping through the ropes, they were finished in brutal fashion in the square ring. What many tend to forget is, in addition to knockout power in either hand, he also had one of the best jabs in the business and skill to back up the power.

Liston was born on 8 May 1932, so the records say. His mother had given estimations of anything from 1927-1932, but the truth is there’s no official documentation that clearly defines the start of his existence. It was Liston himself who created the day he was born in 1953, when he found himself being asked his birthdate when competing in amateur boxing bouts.

Born into a sharecropping family on a farm in Johnson Township, Arkansas, Liston’s father had married twice and had 13 children with his first wife and 12 with his second. Liston was number 24 on the list. So, as one of 25 children it is easy to understand how Liston’s mother, Helen Baskin, might have confused young Sonny’s arrival with one of his siblings. Rumours that he may have been at least five to 10 years older were certainly credible.

Young Sonny suffered countless beatings at the hands of his father Tobe, which left him scarred for life. He was once quoted and saying, ‘The only thing my father ever gave me was a beating.’ When the opportunity came to leave the household and head to St Louis with his mother and a number of siblings in the 1940’s, Liston took it with both hands. Unfortunately for him, with a lack of discipline and education in his life he quickly turned to a life of crime, heading a gang which committed a number of robberies and assaults. His luck however ran out in 1950 when he was convicted for two counts of armed robbery and larceny. On 1 June 1950 he was sentenced to five years in the Missouri State Penitentiary, Jefferson State and it was here that the ring legend was cultivated.

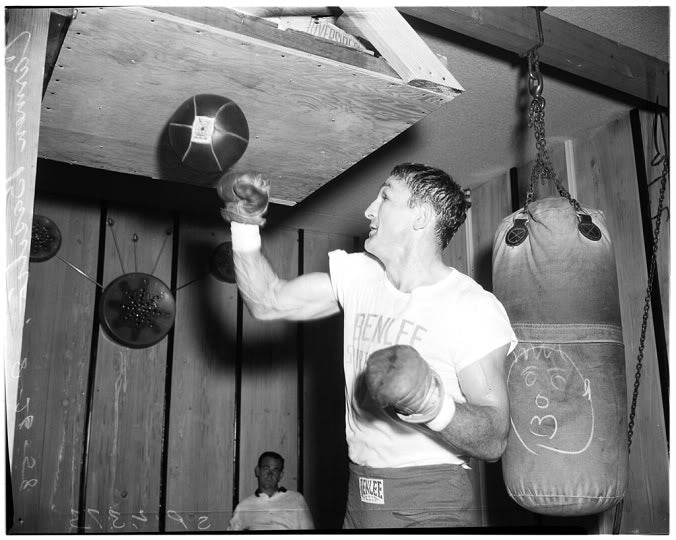

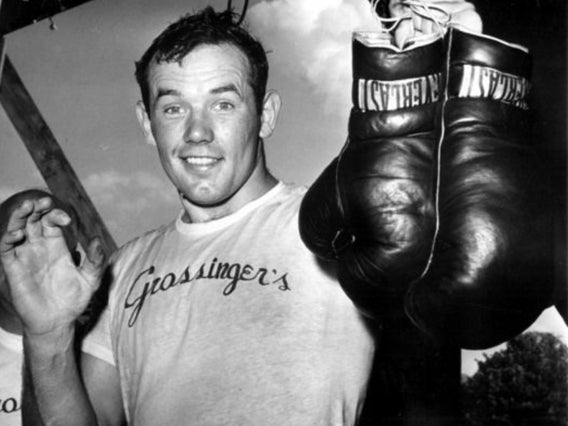

Despite being broke, illiterate and incarcerated, Liston had a pair of guardian angels behind bars by way of the prison’s athletic director, Catholic priest Father Edward Schlattmann and his successor, Reverend Alois Stevens. Schlattmann introduced Liston to the possibility of taking up boxing to channel his aggression. Within a matter of weeks it became evident that Sonny was a force of nature. Reverend Stevens told Sports Illustrated at a later date, ‘He was the most perfect specimen of manhood I had ever seen. Powerful arms, big shoulders. Pretty soon he was knocking out everybody in the gym. His hands were so large! I couldn't believe it. They always had trouble with his gloves, trouble getting them on when his hands were wrapped.’

Through the guidance of both Schlattmann and Stevens, Liston’s commitment to boxing in prison helped to grant him early parole. He was released on 31 October 1952 and taken on board by a group of boxing handlers with direct ties to John Vitale, a well known figure in the underworld. A few years down the line Liston’s management was taken over by two of Las Vegas most prolific criminal bosses, Frankie Carbo and Blinky Palermo. He’d end up fighting under their management banner for 12 fights, but once in their vice like grip, Liston was never a free man again.

Back to the boxing. In less than a year Liston amassed a sensational amateur boxing resume. On 13 Feb 1953, he steamrolled two opponents to win the St Louis Golden Gloves, then took part in the Chicago Golden Gloves Tournament of Champions, beating four fighters over two weeks. His opponent in the final was non-other than the 1952 heavyweight Olympic gold medalist, Ed Sanders. Victory over Sanders certainly started to generate attention for Liston as a future professional hopeful. Over the next three months Liston won the Intercity Golden Gloves Championship, the National AAU Tournament and the International Golden Gloves. Sadly, Ed Sanders died in December 1954, after sustaining a brain injury in a pro fight with Willie James. He was only 24 years old.

Former heavyweight champion Joe Louis with Liston

On 2 September 1953 at the Arena, St Louis weighing a touch over 200lbs and standing 6ft 1inch tall, Liston stopped Don Smith in 33 seconds of the first round. He went on to beat his next six opponents, but on 7 September 1954, Liston lost his first contest to teak tough journeyman, Marty Marshall. Despite knocking Marshall down in the opening round, shortly after he was caught with a right hand and suffered a broken jaw. Liston lasted the distance but lost on a split decision over eight rounds.

Six months later Liston returned, with a comfortable points decision over Neal Welch, then six weeks later he re-matched Marshall, knocking him down four times before the contest was halted in the sixth session. Liston went on to win his next six fights, including a rubber match with Marshall, bringing his record to a respectable 14-1. Unfortunately, Liston’s wayward habits caught up with him again.

On 6 May 1956, Liston and his friend William Patterson beat up a policeman as he was attempting to place a parking ticket on Patterson’s illegally parked taxi. The patrolman, Thomas Mellow, suffered a broken knee and head injuries after the pair claimed Mellow had used racially abusive language towards them. Liston also took the officer’s handgun for good measure, which he returned at a later date. Consequently, on 27 January 1957 Liston pleaded guilty to assault and robbery of a deadly weapon and was sentenced to nine months in prison. Shortly after his release he married Geraldine Chambers, which perhaps added some normality to his life, but unfortunately, his list of misdemeanours and run-ins with the police continued for the next few years. They adopted a son from Sweden, but the pair never had a child themselves, albeit Liston had fathered a number of children out of wedlock.

On 29 January 1958, Liston returned to the ring, knocking out Billy Hunter in two rounds at the Chicago Stadium. The Hunter victory was the first step of Liston’s mission to annihilate the entire heavyweight division. In his first 15 fights eight had gone the distance. Of his next 35 victories, only three would hear the final bell. Nowadays, with his impressive record and punch power, he would have no doubt been granted a title shot in 12-18 months at this stage of his career, but with his known links to the mob and the obvious threat of dethronement for any champion, Liston became an avoided man.

In the meantime, ‘The Night Train,’ now weighing consistently north of 210lbs, started to rack up some very impressive wins on route to challenging for the world title. On 6 August 1958 Liston knocked out Wayne Bethea in a little over a minute of the opening stanza. It’s worth noting that in a 50 fight career, that was Bethea’s only stoppage loss. After disposing of a further four opponents, on 15 April 1959 Liston knocked out highly regarded Cleveland Williams in three rounds, who at the time boasted a record of 45-2 and then four months later flattened Cuban Nino Valdes, also in three rounds.

Between 1960-61, the Arkansas native won a further seven contests, including a re-annihilation of Williams, but in two rounds this time, followed by Zora Folley in three and a wide points decision over Eddie Machen. Having taken on the best in the division, his move towards challenging the reigning heavyweight world champion, Floyd Patterson was now on the immediate horizon.

On 25 September 1962, Liston challenged Patterson at Comiskey Park, Chicago. With Sonny’s criminal past and present mob connections, the fight was almost sold as ‘Good versus Evil,’ with Patterson holding hero status as one of the most liked people in sport. Cus D’Amato, who ironically had mob links himself, did his utmost to steer his charge clear of the fearsome Liston, citing his reasons as not wanting to fight a ‘mob-fighter,’ but the more plausible reason would be his innate fear of Liston demolishing his world champion. If the latter was the case, his fears were justified as Liston smashed Patterson in two minutes and five seconds of the opening round.

Ten months later, on 22 July 1963 Patterson attempted to regain his title at the Convention Centre Las Vegas. With a substantial number of mob figures ringside, Liston floored Patterson three times in the opening round, taking only four more seconds to dispatch the former champion.

Patterson remained active for a further nine years, unsuccessfully challenging for the world title a number of times, but clocking up some impressive victories, including a four round stoppage of our very own Henry Cooper at Wembley and notable wins against George Chuvalo and Oscar Bonavena. His trainer, Cus D’Amato would go on to tutor one of the best heavyweights of all time by way of Michael Gerard Tyson. Imagine how a Liston versus Tyson fight would have panned out at their peaks?

Shortly after, a 22 year old who soon became known as ‘The Louisville Lip’ hounded Liston for a title shot. Cassius Clay had won Olympic gold as a light heavyweight at the 1960 Olympics in Rome, boasted 100-5 as an amateur and was 19-0 as a professional. However, he’d hit the canvas a few times, with his biggest scare happening in his previous fight against Henry Cooper, where his trainer Angelo Dundee saved him, by buying him time. More about that in next month’s BVB article… Either way, boxing’s biggest braggadocio created enough media smoke to land the fight and on 25 February 1964 at the Convention Centre, Miami the pair locked horns.

‘The Big Ugly Bear,’ as Clay had now christened him, weighed in at 218lbs, seven and a half pounds heavier than his challenger. Many believed young Cassius, an 8-1 underdog was in genuine danger of being killed by Liston and that the fight should not have even been sanctioned. However, Clay had other thoughts and said, ‘If you want to lose all your money, be a fool and bet on Sonny.’

From the opening bell, Clay danced and hit Liston at will, as the champion struggled with his trademark elusive style, speed and accuracy. The second round saw Liston land a crunching left hook, hurting his younger adversary and earning him the round on two judges scorecards. Totally undeterred by Liston’s attacks, Clay started launching a barrage of combinations which culminated with a cut under Liston’s left eye. It’s worth noting this was the first time he’d ever suffered a laceration on his face in boxing. As Liston tried to retaliate, he was punching into thin air. By the end of the round he was bruised, battered and deflated.

Round four was shrouded in controversy. As the stanza unfolded Clay kept rubbing his eyes, demonstrating distress with his vision. It’s believed that Liston’s cornerman, Joe Polino had engaged in some skulduggery, rubbing a corrosive substance onto Liston’s gloves. Clay took some heavy blows during the round but managed to steer clear of any damaging shots. His trainer, Hall of Fame inductee Angelo Dundee assessed the situation, cleaned Clay’s eyes with a fresh towel and sent his charge out for round five, with one instruction. ‘Run!’

The younger fighter did well to survive the round, keeping Liston at bay whilst letting the substance in his eyes work its way out of his tear ducts. Come round six, Clay’s vision had cleared and he unleashed hell on the champion. Liston returned to his corner at the end of the round, but never came off his stool. He claimed he’d damaged his shoulder and Clay was declared the winner by TKO. ‘The Greatest,’ was officially born.

The initial date for the rematch was 13 November 1964, but Clay, (now known as Muhammad Ali after his conversion to Islam), three days before the fight reported a strangulated hernia, which delayed the bout until May the following year. The venue was initially agreed to be in Boston on 25 May 1965, but concerns arose that those involved with promoting the event had criminal ties to Massachusetts. Consequently, after a legal dispute, the rematch eventually took place at the Central Maine Civic Centre. However, the change of venue was only sorted out a couple of weeks before fight night and as a result, the show was only attended by 2,434 spectators.

The undercard included Jimmy Ellis and Ali’s younger brother, Rahman who was 2-0 at the time. The main event between Liston and Ali only lasted two minutes and twelve seconds and goes down in history as one of the most controversial endings in the square ring. A little over the halfway mark of the first round, Liston threw his orthodox jab which landed on Ali’s right shoulder. A microsecond later Ali countered with a right hand which looked like it barely landed and Liston hit the canvas for the full 10 count. The blow would be engrained in boxing folklore as ‘The Phantom Punch,’ as many believed Liston had taken a dive for the mob.

Liston vs Ali 2

The controversy wasn’t over yet. The referee was non-other than former heavyweight champion, Jersey Joe Walcott and while Ali was standing over Liston shouting, ‘Get up and fight, sucker,’ Walcott had not started the count. Instead, once Liston rose to his feet, Walcott wiped his gloves and motioned the fighters to continue fighting. Ring magazine Editor, Nat Fleischer was screaming at Walcott that the 10 count had passed, which led him to jump over to the fighters and declare the contest over.

Following the Ali loss, Liston struggled to become financially fluid. He fought to put food on the table, but still kept mob ties and lived a life which involved, drugs, alcohol and shady figures from all walks of life. Liston found it difficult to walk away from the gutter, as one of boxing’s most sensational heavyweight figures.

After a year of inactivity Liston returned to the ring on 1 July 1966 in Stockholm, knocking out German Gerhard Zech in seven rounds. His next three fights, also in Sweden, we’re under the promotional banner of former champion, Ingemar Johansson and he delighted fans again with three knockout victories.

Liston vs Wepner

In the next 30 months Liston clocked up a further 10 victories before suffering his fourth and final defeat at the hands of his old sparring partner, Leotis Martin. Liston’s final fight was against the man who inspired the Rocky movies, Chuck Wepner. After knocking Wepner down in the fifth with a body shot, ‘The Bayonne Bleeder,’ lasted four more rounds, before the referee stopped the fight due to the number of cuts on his face. Living up to his moniker, it was rumoured that Wepner required over 100 stitches after the fight. Wepner, along with Ali and countless others claimed Liston was the hardest puncher they’d ever shared a ring with.

Next up was the Canadian heavyweight champion George Chuvalo. Unfortunately, the fight never happened. On 5 January 1971, Liston’s wife Geraldine returned to their Las Vegas residence after having visited her mother for two weeks. On entering the house with her seven-year-old son, the front door was unlocked and she was greeted by a foul smell, which she soon discovered to be coming from the principal bedroom upstairs. On opening the door, she discovered the source was her decaying husband, who was slumped up against the bed in his underwear and a t shirt, with the remnants of dried, crusted blood around his nostrils. It is believed he had been dead for about a week, which reflects the commonly circulated date of passing as 30 December 1970. Like the rematch with Ali, this final episode of Liston’s life was surrounded with huge controversy.

Sergeant Dennis Caputo was the first on the scene and reportedly discovered heroin and marijuana on site. There are various theories as to how Liston perished, but one angle which made little sense was heroin overdose via syringe. It was common knowledge that Liston had a massive fear of needles and at the scene there was no torniquet for his arm or any needles. Needle marks were found on his arm, and the more credible theory was that Liston was overwhelmed by a group of people, held down, injected and then left to die. The presence of a broken foot bench on the floor perhaps indicates Liston falling during the struggle. Did the mob kill him because he knew too much, or perhaps because he was no longer of use to their operations? Maybe he became resistant to their requests? Did the police or the mob sweep the house for evidence and leave Liston to rot? Who knows.

The police publicised the theory that family and friends had cleaned up the scene before they arrived, removing items such as a torniquet or needles to save any further embarrassment for Liston. Sergeant Caputo declared Liston’s death as heroin overdose. Interestingly, in the post-mortem heroin was found in Liston’s blood stream, but according to the report, not in a quantity large enough to have killed him. The official ruling of Liston’s death was recorded as natural causes, by way of heart failure and lung congestion Why and how he died will forever be one of boxing’s biggest mysteries.

His funeral was attended by over 700 people, including Sammy Davis Jr, Doris Day, Sugar Ray Robinson, Joe Louis and of course, his arch-rival, Muhammad Ali. In a 17 year professional career, Liston racked up 50 wins and only four losses. He was inducted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame in 1991 and without a doubt would have given any heavyweight of any era as much trouble as they could handle.

Paradise Memorial Gardens is close to McCarran airport, Las Vegas. On departure from Sin City, one of the last headstones you will fly over reads, Charles ‘Sonny’ Liston. 1932-1970. ‘A Man.’

Paul Zanon, has had 11 books published, with almost all of them reaching the No1 Bestselling spot in their respective categories on Amazon. He has co-hosted boxing shows on Talk Sport, been a pundit on London Live, Boxnation and has contributed to a number of boxing publications, including, Boxing Monthly, The Ring, Daily Sport, Boxing News, Boxing Social, amongst other publications.