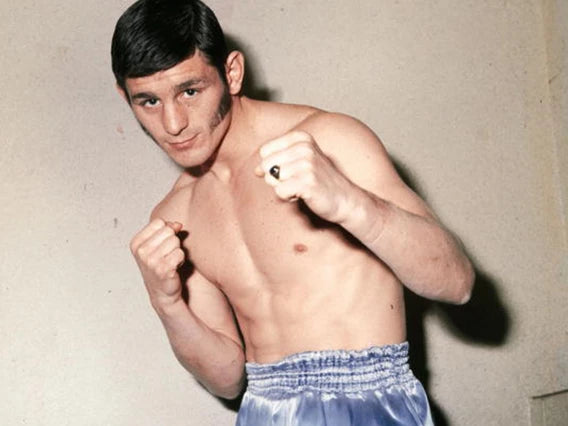

Jean Pierre Famechon, or ‘Fammo,’ as he was known by most of the punching population of Australia, was born to French parents Antoinette and Andre on 28 March 1945, in Paris. At the age of five his family relocated to Australia, settling eventually in Melbourne.

The boxing gene was certainly in the Famechon bloodline. Johnny’s uncle, Emile held the French flyweight title, while his father became French lightweight champion and finished with a very respectable record of 60-20-9, over an eight year career. However, his uncle Ray was another level, losing only 14 in 117 fights, during which time he became French featherweight champion in his first six months as a pro, then went on to gain European honours, holding the strap for a number of years. Notable losses came against Sandy Sadler and a gallant effort against Willie Pep, unsuccessfully challenging for the world crown.

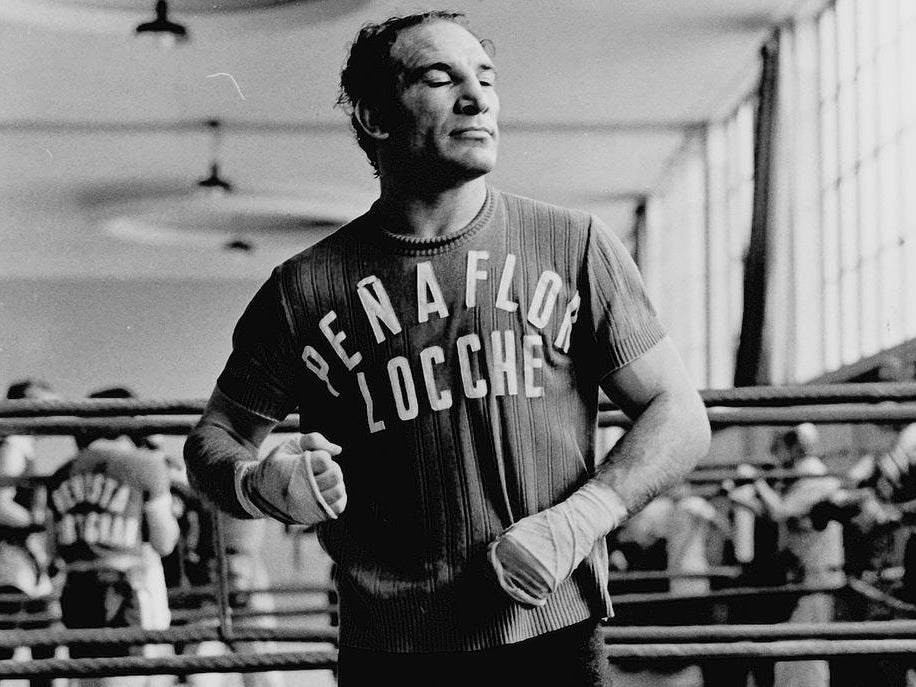

Young Johnny started training at Ambrose Palmer’s gym in West Melbourne, which was situated under the Festival Hall. The site would become a spiritual home of sorts for Famechon in the coming years. Palmer had clocked up 83 games as a professional Australian rules football player over an 11-year career, however, boxing was his true calling. In addition to coaching the Australian boxing team at the 1956 Olympics in Melbourne, Palmer went on to receive a number of plaudits over the years including an MBE for services to sport. Under Palmer’s guidance, Famechon was moulded into the great defensive fighter everyone remembers him for.

With no amateur experience, Fammo turned pro at only 16 years of age on 9 June 1961, at the Festival Hall, Melbourne. In fact, in a 69-fight career, 55 of his contests would be at the very same venue, which explained the incredible support he always received from his hometown.

Famechon made his debut at super flyweight and spent the next 12 months growing into his natural featherweight frame, albeit, his first six fights reflected results of an inexperienced boxer who was still learning on the job – which was technically very true of him. Winning three, losing two and drawing one, Fammo found his feet at the end of 1962 and won his next 19 outings, which included winning the Victoria State featherweight championship and swiftly after, the Australian featherweight strap.

By 1 April 1965, Famechon was 21-1-1 and showed he had earned the right to step up in competition. Unfortunately, his next seven fights contradicted this statement. Despite winning three fights, he lost three and drew won. By 29 October 1965, Famechon’s loss against Italian born Aussie, Gilberto Biondi, left him with a record of 24-4-2. Thankfully, he wouldn’t lose again until 1970.

On 24 November 1967, the Melbourne favourite took on the reigning Commonwealth featherweight champion, Glaswegian John O’Brien. In a pitch perfect performance from Famechon, the contest was stopped in the eleventh round due to injuries sustained to O’Brien’s eye.

The Parisian born 126lbs fighter went unbeaten in his next eight contests, before being handed the opportunity all fighters dream of. On 21 January 1969, Famechon took on WBC world featherweight champion, Cuban born Jose Legra. Despite having started his pro career 12 months prior to Famechon, the Spanish resident had already amassed 114 fights, having lost only five. In the previous 13 months Legra had won the European title, stopping Yves Desmarets in three rounds and a few months later stopped the WBC world featherweight champion Howard Winstone in five. This was without a doubt Famechon’s toughest test by a country mile.

Famechon wins the WBC featherweight title from Legra 1969

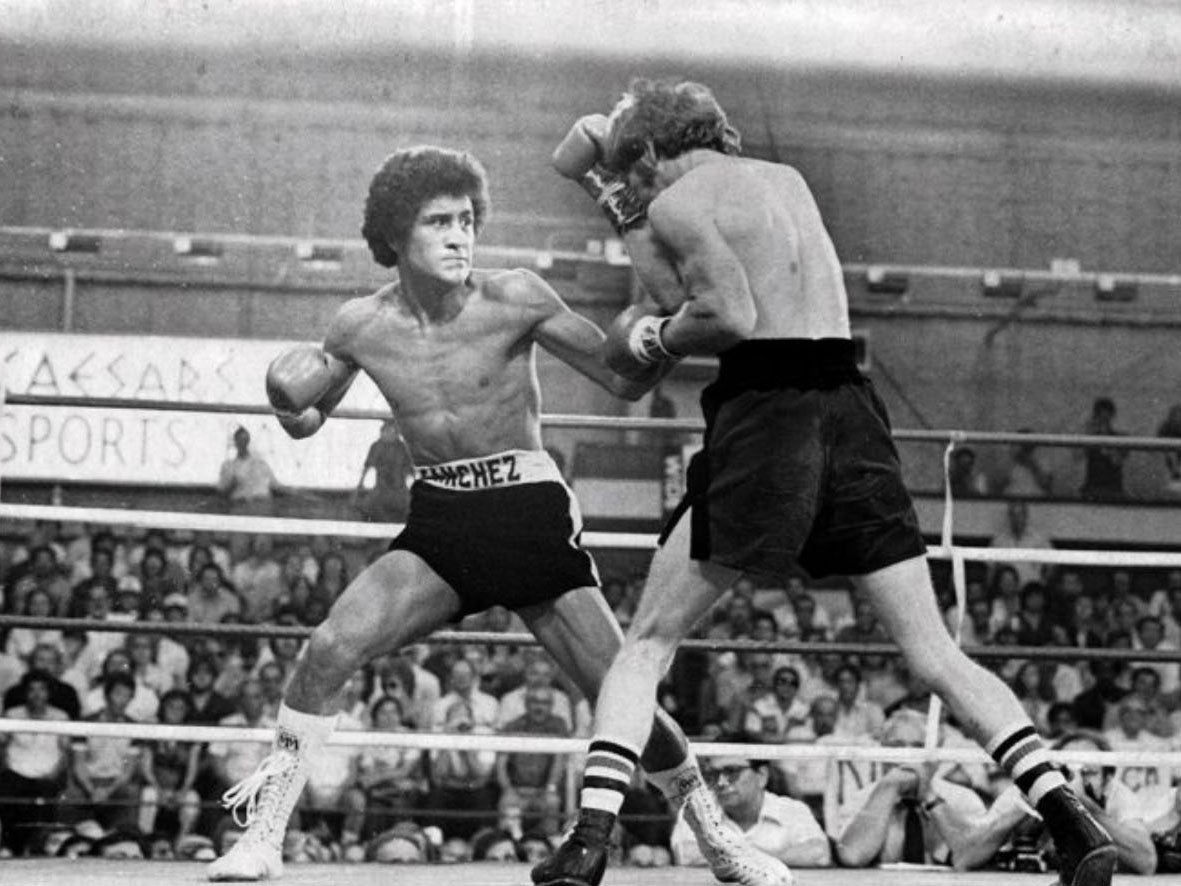

Wearing a tailored pair of his father’s light blue boxing trunks, Fammo took on the man known by many as the ‘Mini Cassius Clay,’ at the Royal Albert Hall, London. All eyes were firmly fixed on the Aussie as he made his debut off home soil, with bookies betting against him to the power of 6-1.

Despite being shorter by almost three inches and the obvious underdog, Famechon was unphased by the confident champion and used his footwork, jab and combinations to frustrate Legra, who was hunting the challenger down. As Legra attacked, Fammo made him miss, then made him pay with some beautiful counter punching. It wasn’t a landslide victory for either fighter going into the final rounds and when the bell sounded for the start of the fifteenth, both Legra and Famechon knew that winning the final stanza could tip the decision their way.

While Cuban went for the knockout, the Aussie stayed calm, countering and delivering the cleaner, more eye catching shots for the referee to judge. After 45 minutes of action, Famechon won 74 ½ to 73 ¼. He was the new WBC featherweight champion of the world.

In the next four months, Famechon won three fights, however, his first real test since Legra was against legendary Japanese bantamweight champion, Fighting Harada on 28 July 1969. Fighting in front of a packed crowd at Sydney Stadium, with non-other than Willie Pep as referee, Famechon clinched a very tight points victory against the Tokyo resident.

Capping off 1969 with two fights in four weeks at the Albert Hall, on 6 January 1970, Fammo and Harada met once more, but this time at the Metropolitan Gym in Tokyo. Comfortably ahead on all three scorecards, Famechon stopped the future hall of famer in the fourteenth round.

Three months later, he travelled to Ellis Park, Johannesburg, beating Arnold Taylor on points, before losing a very close points decision and his world featherweight crown against Mexican Vicente Saldivar, at the Palazzetto Dello Sport in Rome. At only 25 years of age and still in great condition, many were surprised that he decided to retire soon after this fight. With money in the bank and health on his side, he never made a comeback.

Famechon invested in a number of businesses, took on a variety of working roles and was often seen around boxing circles in a refereeing capacity. Despite a decorated career against some heavy hitters, his biggest fight happened in 1991 while out for a jog by Sydney’s Warwick Farm racecourse, when he was hit by a car doing in excess of 60 mph. At the moment of impact, the former featherweight king was sent flying into the air and sustained brain injuries.

After a three week coma, he went through a battery of rehabilitation at a number of facilities in Melbourne and Sydney, before succumbing to a stroke. Unable to walk and talk at this point, the prognosis from the medical experts was that Famechon’s life would be severely compromised moving forward and his level of recovery would be hopeful at best.

In 1993, Fammo and his girlfriend Glenys, who he had only met the year before, were introduced to a gentleman by the name of Ragnar Purje. The future award winning neuroscientist was an Australian karate champion, practising a particular discipline called Goju Ryu, however, it was his radical ideas connected to physical movement to help improve Famechon’s brain function which proved to be a game changer.

In an interview with ABC News, Purje said, ‘I spent three hours with John and Glenys that first meeting and I could not believe how articulate John was, even though he had immense difficulty talking.’ After weeks of engaging with Fammo, putting him through a variety of physical exercises, the fighting featherweight went from struggling to whisper, to putting together words, then full sentences. Physically, he went from a wheelchair, to a crawl and then a walk. Purje’s work with Famechon lead him to write a thesis 20 years later, which focused on the success of his pioneering neurological acquired brain injury rehabilitation therapy, now referred to Complex Brain-Based Multi-Movement Therapy. Dr Purje was indeed a miracle worker.

Famechon was inducted into the Australian Sports Hall of Fame in 1985 and the International Boxing Hall of Fame in 1997. The same year, four years after the accident, Famechon walked unassisted down the aisle and married his beloved Glenys. More recently, in 2022 he was awarded the Member of the Order of Australia, at the Queen’s Birthday Honours, for his service to boxing.

With his distinctive mutton-chop sideburns, Johnny Famechon fought from 1961 – 1970 and was never stopped in 69 contests. Of his five defeats, he avenged four, the only one he didn’t was against Saldivar, which many believed he could won in the rematch. After Jimmy Carruthers and Lionel Rose, Famechon was Australia’s third ever world champion.

Johnny Famechon passed away on 4 August 2022 in Melbourne. If you didn’t have the pleasure of meeting him in person, a 2.5 metre bronze statue is on display for you to see, at Ballam Park. The statue was unveiled on 21 January 2018, exactly 49 years to the day he beat Legra for the world title. Known as ‘Poetry in Motion,’ and ‘The Artful Dodger,’ in the square ring, Famechon’s spirit will live on for many years to come.

Paul Zanon, has had 11 books published, with almost all of them reaching the No1 Bestselling spot in their respective categories on Amazon. He has co-hosted boxing shows on Talk Sport, been a pundit on London Live, Boxnation and has contributed to a number of boxing publications, including, Boxing Monthly, The Ring, Daily Sport, Boxing News, Boxing Social, amongst other publications.